Alebrijes

Oaxacan Wood Carvings

Hand-carved and then painted in cheerful colors, these alebrije carvings are the most sought-after folk art in Mexico. Each finely-crafted sculpture reflects its maker’s talent and imagination. We buy our figurines directly from carvers living in villages of the Oaxaca valley. Most are signed by the artists. In most wood-carving families, the husband does the carving and whittling, children sand the figurines to a smooth finish, and it is often the wives who paint the finely-detailed patterns. The realm of Oaxacan woodcarving reflects the best of Mexico’s wonderful, “made-by-hand” artistic traditions.

Read More About Alebrijes

Alebrijes – Colorful Folk Art Wood Carvings from Oaxaca

Alebrijes, the vivid and whimsical wooden figures handmade by artisans in Oaxaca, are the most prized of all the Mexican crafts. They are a subset of a wide range of Oaxaca carvings. They are typically the most colorful, the most outlandish, imaginary and fantastical of the Oaxacan carvings. These are painted with the most detailed patterns of stripes, dots, geometric shapes, flowers and flames. Sometimes the creature will have two heads. Sometimes it has the face of a lion and feet of a flamingo. Any strange combination of species and body parts is fair game. If it lives in an artist’s dreams or hallucinations, it’s probably an alebrije.

Mexican craft traditions date back to the 1500s, evolved from the fusion of the ancient indigenous techniques and design with those of the conquering Spanish. The art of the alebrijes is far more recent.

Where does the term “alebrije” come from?

The original figures sprung from a series of fevered, hallucinatory dreams that a 30-year-old Mexican papier-maché artist, Pedro Linares, had in 1936. In his dreams, these strange creatures would chant at him with a word he later recalled as “alebrije. Later, recovered from his illness, the artist started crafting these large, strange creatures in papier-maché. It wasn’t long before these wild figures caught the attention of a gallery owner in Cuernavaca. Soon his work was acclaimed by the likes of Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera, who commissioned him to make more. Eventually, Linares’ work was celebrated throughout Mexico. Before his death in 1992, he was Mexico’s National Arts and Sciences Award in Popular Arts and Traditions.

Meet Manuel Jimenez, originator of the Oaxacan alebrije carvings

Down in Southern Mexico, in the village of Arrazola, which sits at the foot of the famed Monte Alban archaeological site, a peasant named Manuel Jiménez had been carving wood figures since his boyhood in the 1920s. His early figures were masks and small farm animals, which he would often sell outside the gates to Monte Alban. In the 1970s, after having an opportunity to meet Linares, Jimenez started to add the fantastical elements of the alebrijes to his carvings, which he was now making out of softwood from a scrub tree called copal. The effect revolutionized the carving craft. Jimenez quickly found a ready market for his figures in the street markets of Oaxaca City. Eventually the carving caught on with farmers and campesinos in other towns — La Union Tejalapam and San Martin Tilcajete. Soon, the wooden creatures became sought-after by collectors throughout North America and beyond. After Smithsonian Magazine did a cover story on alebrijes in 1987, they became widely seen as traditional Oaxacan folk art creations.

Carvers Of Today

Today, most carvers are not Zapotec, and the art form is neither centuries’ old nor a creation of indigenous peoples. Yet Oaxacan wood carvings are the most celebrated and collected of all Mexican Folk Art. Interesting, the raw material, copal wood, has other uses that do go back to ancient times. The sap is used for an array of medical purposes, such as treating scorpion bites, relieving acne and treating cold symptoms. The hardened resin is also burned in churches and cemeteries during religious services with the smoke producing a distinctive fruity fragrance. Burning copal resin is an essential part of both ancient and modern Day of the Dead celebrations.

There is an interesting division of labor that I have seen repeatedly within the families making Oaxacan carvings. The gathering, chopping and carving of the wood is done by males, both men and boys. After the initial rough carving, the wood is left to day, often for several months. Then the sanding, a low-skill and boring part of the job, is done by children. The most creative and painstaking part, the elaborate and delicate painting of the figures, is done by women. In decades past, the carvings were signed only by the male head of the family. I have noticed a nice trend in recent years that more and more of the carvings bear the names of both the husband and wife.

Phil Saviano

Showing all 10 results

-

Nahual Dog Tuba Player

Size: 9.5 inches tall

Nahual Dog Tuba Player is a Oaxacan wood carving by Juventino Melchor. Each one is painted in unique color patterns. Colors may differ from that shown.

SKU: WD-6_09$59.00 -

Nahual Burro

Size: 8.5 inches tall

The Nahual Burro is a bold blue color with wings edged in green and brown. Handmade by Avelino Perez and signed by the artist.

SKU: WD-6_12$78.00 -

Toucan Playing Maracas Nahual

Size: 7.5 inches tall

Toucan Playing Maracas Nahual. This Oaxacan wood carving is by Juventino Melchor. Colors may vary.

SKU: WD-6_13$59.00 -

Fox Alebrije Carving

Size: 7 inches long x 7 inches tall

This Fox Alebrije carving is handmade by Taller de Mario Castellanos. It is beautifully painted in shades of lavender and green with an intricate geometric design.

SKU: WD-2_01$265.00 -

Honeybee Wood Carving

Size: 8 inches long x 8.5 inches tall

This Honeybee Wood Carving is handcrafted in Oaxaca by the Blas Family. Each honeybee is one of a kind so colors will vary. Wings and legs detach for safe shipping.

SKU: WD-5_02$59.00 -

Sale!

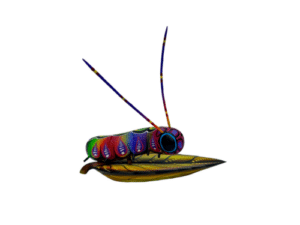

Caterpillar On A Leaf

Size: 7 inches long

This Caterpillar On A Leaf is colorful and adorable. The Oaxacan Wood Carving figurine is made by Blas Alebrijes. It disassembles for safe shipping.

SKU: WD-5_08$44.00 -

Coatlique Dragon, Oaxaca Alebrije by Blas family, 11-inch tall

Size: 11 inches tall x 10 inches long

The whimsical coatlique dragon Oaxacan carving is painted in brilliant shades of lavender, red and green. It is one-of-a-kind, and signed by the artist, Melisio Blas. Wings detach for safe shipping. Note: This item is considered oversized and does not qualify for free shipping.

SKU: WD-9_01$109.00 -

Serpent Alebrije No. 1

Size: 16.5 inches tall x 14.5 inches long x 19 inches wide

The Serpent Alebrije is a fantasy serpent with wings, a pointed tail, and a mane that surrounds the serpent’s head. It is multi-colored with beautiful, highly detailed designs. The eyes are fiery yellow and it has jagged teeth. The wings and feathers detach for safe shipping. By Taller Tribus Mixes. Note: This item is considered oversized and does not qualify for free shipping.

SKU: WD-1_010$290.00 -

Serpent Alebrije No. 3

Size: 15.5 inches tall x 14.5 inches long x 21 inches wide

The Serpent Alebrije is a fantasy serpent with wings, a pointed tail, and a mane that surrounds the serpent’s head. The body and wings are painted in black, white, metallic silver and metallic gold. The feathers on the wings are purple, orange, and blue. It is beautiful, highly detailed designs. The eyes are fiery orange and it has jagged teeth. The wings and feathers detach for safe shipping. By Taller Tribus Mixes, it is signed. Note: This item is considered oversized and does not qualify for free shipping.

SKU: WD-1_016$280.00 -

Orange Dragon

Size: 10 inches tall x 12 inches long x 9.5 inches wide

The orange dragon is painted in dark orange and mustard colors. The intricate design mimics the scales of a lizard. The spikes on the back are painted a metallic gold and the spike under the chin is a metallic silver. It has green eyes. The ears, wings, and tongue detach for safe shipping. Signed by the artist, Taller Tribus Mixes.

SKU: WD-1_017$150.00